Positive policing changes after cannabis legalization

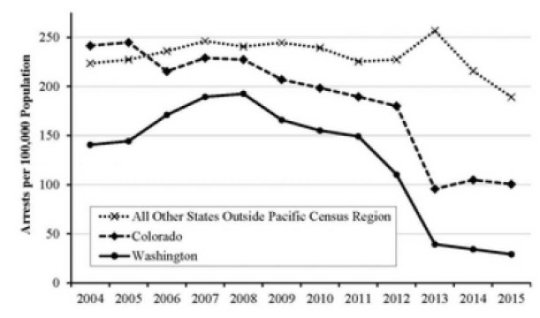

Marijuana arrest rates were already on the decline but plummeted after Colorado and Washington authorized retail sales late in 2012. Credit: David Makin, Washington State University

July 24, 2018

Science Daily/Washington State University

Washington State University researchers have found that marijuana legalization in Colorado and Washington has not hurt police effectiveness. In fact, clearance rates for certain crimes have improved.

Clearance rates -- the number of cases solved, typically by the arrest of a suspect -- were falling for violent and property crimes in the two states before they authorized retail sales of marijuana late in 2012. The rates then improved significantly in Colorado and Washington while remaining essentially unchanged in the rest of the nation, according to the researchers' analysis of monthly FBI data from 2010 through 2015.

"Our results show that legalization did not have a negative impact on clearance rates in Washington or Colorado," said David Makin assistant professor in WSU's Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology "In fact, for specific crimes it showed a demonstrated, significant improvement on those clearance rates, specifically within the realm of property crime."

Writing this month in the journal Police Quarterly the researchers said legalization created a "natural experiment" to study the effects of a sweeping policy change on public health and safety.

"If you think about our history, it's rare where you have something that is entirely illegal that then becomes legal," said Makin. "And we have an opportune moment to study to what extent that particular change had on society."

Citizens in 12 states have voted on marijuana legalization and proponents in all of them have argued that it would let police reallocate resources to property and violent crimes. The Colorado measure specifically says it is "in the interest of the efficient use of law enforcement resources" while the Washington one says it "allows law enforcement resources to be focused on violent and property crimes."

The WSU study bears that out. It finds that after legalization:

· Arrest rates for marijuana possession dropped considerably. Following legalization in 2012, they dropped nearly 50 percent in Colorado and more than 50 percent in Washington.

· Violent crime clearance rates shifted upward.

· Burglary and motor vehicle theft clearance rates "increased dramatically."

· Overall property crime clearance rates jumped sharply and reversed a down ward trend in Colorado.

The improvement in burglary clearance rates is particularly striking for Washington, Makin said, as the state's property crime rate is higher than most.

"It demonstrates just how critical these types of policy changes can be," Makin said. "I would offer it truly demonstrates why we need empirical data to support these types of studies, so we can understand to what extent crime and communities are influenced as more and more states move to legalization."

As Makin describes, this research is not without its limitations. He offers "one of the pressing limitations within this study is that not all agencies equally report their clearance rates. It is entirely possible that as we expand our data collection to include additional years, more states, and a wider set of agencies, these results could change."

Makin also acknowledged that while he and his colleagues found a correlation between legalization and clearance rates, they do not have an explicit cause. The improvements could be the result of more overtime for law enforcement officers, new strategies or a focus on particular crimes. But Makin said he suspects that the loss of the specific reporting category of marijuana arrests prompted police departments to reevaluate their priorities, particularly in "boots on the ground" cases.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/07/180724110031.htm

Oregon's marijuana legalization prompted big drop in sales in Washington's border counties

Economists find a reduction of legally purchased pot products moving illegally out of Washington

September 5, 2017

Science Daily/University of Oregon

Three days after recreational marijuana sales became legal in Oregon, sales across the border in Washington, where retail availability already existed, dropped by 41 percent, reports a team of University of Oregon economists.

The study also suggests that illegal cross-border movement, or diversion, of legally produced marijuana sold at retail outlets across state borders is a real concern but not occurring at alarming levels.

The National Bureau of Economic Research published the study this week as part of its working papers series.

"We found that the majority of marijuana sold in Washington is actually staying there," said study co-author Benjamin Hansen, a health economist at the UO. "We found that prior to Oregon's legalization 11.9 percent was potentially being diverted out of Washington overall, and it dropped to 7.5 percent after Oregon's legalization."

The research tapped a naturally occurring experiment to explore the issue of small-scale trafficking due to cross-border shopping by Oregon residents in Washington, said Caroline Weber, a professor in the UO's Department of Economics.

Washington was one of the first states to legalize recreational marijuana. The state's regulatory and tracking requirements covering production to sales provided a wealth of data, she said. The UO team studied Washington's sales for the two months before and after Oregon's legal market opened on Oct. 1, 2015.

In doing so, researchers were able to address one of the key concerns of the Cole Memorandum issued in 2013 by then-Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole. It called for federal law enforcement officials to monitor the diversion of sales across borders as states moved to legalize medical and recreational marijuana.

"There has been a lot of debate about a federal crackdown on marijuana," Hansen said, referring to signals expressed by the Trump Administration. "Our study says that 93 percent of marijuana sold in Washington is probably staying there now. There's probably not a lot you can do about the remaining share that is being diverted at this point. This is just the likely consequence of partial prohibition."

The diversion data also included the flow of retail-sold marijuana in Washington to neighboring Idaho and to British Columbia.

Because federal law still classifies marijuana as a Schedule 1 drug, grouped with heroin and methamphetamines, illegal cross-border movement could be targeted by law enforcement. One such method is by using randomized traffic searches along state borders.

Prior to Oregon's market opening, an average of 1,662 retail sales transactions occurred daily in Washington's Clark and Klickitat counties, just across the Columbia River from Portland. Given that 293,840 vehicles went between Oregon and those counties daily in 2015, according to the Oregon Department of Transportation, "a policy of randomly searching border-crossing vehicles could expect to find diverted recreational marijuana in just 0.47 percent of stops," the researchers concluded.

"You might expect larger diversion when states around a legalized one are not allowing recreational or medical market sales," Hansen said, adding that California, based on this study, likely will experience far less diversion because all of its neighboring states allow for some form of legal marijuana use.

The analysis by the team, which also included UO economist Keaton Miller, also found that randomized searches along Washington's Spokane and Whitman counties with Idaho, where marijuana is illegal, might expect to find illegally transported marijuana at most 4 percent of the time.

In the two months prior to the opening of Oregon's recreational market, 5,624 kilograms (12,398 pounds) of marijuana were sold in Washington; 670 kilograms (1,477 pounds), or 11.9 percent, went across state lines. Factoring in the 41 percent drop in sales along the Oregon border and no decline elsewhere in Washington implies that only 7.5 percent is illegally leaving Washington today, the research team concluded.

"Given the data available, we've been able to study this natural experiment to speak to a question that a lot of people in law enforcement and government care about," Weber said. "If we had instead found that 60 percent of Washington's marijuana was being diverted, then it would have suggested a whole different approach to thinking about legalization moving forward."

Small amounts of illegal, small-scale trafficking is to be expected as long as the U.S. does not have uniform policies, Hansen said.

Based on the data, the researchers concluded, people seem to prefer purchasing recreational marijuana in legal recreational markets instead of through the black market or as medical marijuana or growing their own.

"People value being able to go to a store, seeing the variety of products that are offered there and purchasing it in a retail store," Weber said.

Paper access: http://www.nber.org/papers/w23762

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/09/170905134452.htm