Smoking marijuana provides more pain relief for men than women

August 18, 2016

Science Daily/Columbia University Medical Center

Men had greater pain relief than women after smoking marijuana, a new study has found. Despite differences in pain relief, men and women did not report differences in how intoxicated they felt or how much they liked the effect of the active cannabis.

Researchers from Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) found that men had greater pain relief than women after smoking marijuana.

Results of the study were recently published online in Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

"These findings come at a time when more people, including women, are turning to the use of medical cannabis for pain relief," said Ziva Cooper, PhD, associate professor of clinical neurobiology (in psychiatry) at CUMC. "Preclinical evidence has suggested that the experience of pain relief from cannabis-related products may vary between sexes, but no studies have been done to see if this is true in humans."

In this study, the researchers analyzed data from two double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies looking at the analgesic effects of cannabis in 42 recreational marijuana smokers. After smoking the same amount of either an active or placebo form of cannabis, the participants immersed one hand in a a cold-water bath until the pain could no longer be tolerated. Following the immersion, the participants answered a short pain questionnaire.

After smoking active cannabis, men reported a significant decrease in pain sensitivity and an increase in pain tolerance. Women did not experience a significant decrease in pain sensitivity, although they reported a small increase in pain tolerance shortly after smoking.

Despite differences in pain relief, men and women did not report differences in how intoxicated they felt or how much they liked the effect of the active cannabis.

The authors noted that additional studies in both men and women are needed to understand the factors that impact the analgesic effects of cannabinoids, the active chemicals in cannabis products, including strength, mode of delivery (smoked versus oral), frequency of use and type of pain measured.

"This study underscores the importance of including both men and women in clinical trials aimed at understanding the potential therapeutic and negative effects of cannabis, particularly as more people use cannabinoid products for recreational or medical purposes," said Dr. Cooper.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160818165936.htm

First study to explore language and LSD since the 1960s: New study shows LSD's effects on language

August 18, 2016

Science Daily/Technische Universität Kaiserslautern

The consumption of LSD, short for lysergic acid diethylamide, can produce altered states of consciousness. This can lead to a loss of boundaries between the self and the environment, as might occur in certain psychiatric illnesses. David Nutt, professor of Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College, leads a team of researchers who study how this psychedelic substance works in the brain.

In this study, Dr. Neiloufar Family, post-doc from the University of Kaiserslautern, investigates how LSD can affect speech and language. She asked ten participants to name a sequence of pictures both under placebo and under the effects of LSD, one week apart.

"Results showed that while LSD does not affect reaction times," explains lead author Neiloufar Family, "people under LSD made more mistakes that were similar in meaning to the pictures they saw." For example, when people saw a picture of a car, they would accidentally say 'bus' or 'train' more often under LSD than under placebo. This indicates that LSD seems to effect the mind's semantic networks, or how words and concepts are stored in relation to each other. When LSD makes the network activation stronger, more words from the same family of meanings come to mind.

The results from this experiment can lead to a better understanding of the neurobiological basis of semantic network activation. Neiloufar Family explains further implication: "These findings are relevant for the renewed exploration of psychedelic psychotherapy, which are being developed for depression and other mental illnesses. The effects of LSD on language can result in a cascade of associations that allow quicker access to far away concepts stored in the mind."

The many potential uses of this class of substances are under scientific debate. "Inducing a hyper-associative state may have implications for the enhancement of creativity," Family adds. The increase in activation of semantic networks can lead distant or even subconscious thoughts and concepts to come to the surface.

This article was published in the academic journal Language, Cognition and Neuroscience under the title: "Semantic activation in LSD: evidence from picture naming."

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160818090035.htm

Why scientists are calling for experiments on ecstasy

July 14, 2016

Science Daily/Cell Press

MDMA, more commonly known as ecstasy, promotes strong feelings of empathy in users and is classified as a Schedule 1 drug--a category reserved for compounds with no accepted medical use and a high abuse potential. But in a Commentary published July 14 in Cell, two researchers call for a rigorous scientific exploration of MDMA's effects to identify precisely how the drug works, the data from which could be used to develop therapeutic compounds.

"We've learned a lot about the nervous system from understanding how drugs work in the brain--both therapeutic and illicit drugs," says Robert Malenka, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Stanford University. "If we start understanding MDMA's molecular targets better, and the biotech and pharmaceutical industries pay attention, it may lead to the development of drugs that maintain the potential therapeutic effects for disorders like autism or PTSD but have less abuse liability."

MDMA is described as an "empathogen," a compound that promotes feelings of empathy and close positive social feelings in users. The drug is a strictly regulated Schedule I compound, along with drugs such as heroin and LSD. However, MDMA's regulated status shouldn't discourage researchers from studying its effects, argue Malenka and coauthor Boris Heifets, also at Stanford.

Researchers still don't know exactly how MDMA works in humans, what regions of the brain it targets, or all of the molecular pathways it affects. Malenka and Heifets don't condone the drug's recreational use, but say that scientific study to uncover its mechanisms could help explain fundamental workings of the human nervous system--including how and why we experience empathy. Early clinical cases and a small trial in 2013 also showed some use for MDMA as a treatment during therapy for patients with PTSD, possibly aiding patients in forming a stronger bond with a therapist.

"Studying the response of the brain and nervous system to any drug is no different than running an animal through a maze and asking how learning and memory work, for example," Malenka says. "You're trying to understand the different mechanisms of an experience. Drugs like MDMA should be the object of rigorous scientific study, and should not necessarily be demonized."

The advent of tools over the last decade such as optogenetics, viral tracing methodologies, sophisticated molecular genetic techniques, and the ability to create knockout mice have contributed to the push for more research into MDMA. "I started thinking five or six years ago that maybe we can actually attack how MDMA works in the brain in a more meaningful way, because now we have the tools to do it right," says Malenka.

Malenka's team has already begun preliminary studies to test MDMA's effects in mice, and is writing a proposal to the National Institute on Drug Abuse for a larger project in concert with researchers who plan to tackle the human aspects of the study. Studies using MDMA have to go through many rounds of paperwork and follow stringent safety measures to get approval, but Malenka's message is clear: it's worth it.

"There are going to be certain areas of the brain in which MDMA's actions are critical for its behavioral effects," says Malenka. "You can give it to human beings under appropriately controlled, carefully monitored clinical conditions and do fMRI and funcational connectivity studies, and you can begin to build up a knowledge base in an iterative fashion, combining the animal and human studies, where we start to gain more traction in understanding its neural mechanisms."

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/07/160714134748.htm

Magic mushroom compound psilocybin could provide new avenue for antidepressant research

May 17, 2016

Science Daily/The Lancet

Psilocybin -- a hallucinogenic compound derived from magic mushrooms -- may offer a possible new avenue for antidepressant research, according to a new study published in The Lancet Psychiatry today.

The small feasibility trial, which involved 12 people with treatment-resistant depression, found that psilocybin was safe and well-tolerated and that, when given alongside supportive therapy, helped reduce symptoms of depression in about half of the participants at 3 months post-treatment. The authors warn that strong conclusions cannot be made about the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin but the findings show that more research in this field is now needed.

"This is the first time that psilocybin has been investigated as a potential treatment for major depression," says lead author Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, Imperial College London, London, UK. "Treatment-resistant depression is common, disabling and extremely difficult to treat. New treatments are urgently needed, and our study shows that psilocybin is a promising area of future research. The results are encouraging and we now need larger trials to understand whether the effects we saw in this study translate into long-term benefits, and to study how psilocybin compares to other current treatments."

Depression is a major public health burden, affecting millions of people worldwide and costing the US alone over $200 billion per year. The most common treatments for depression are cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and antidepressants. However, 1 in 5 patients with depression do not respond to any intervention, and many relapse.

"Previous animal and human brain imaging studies have suggested that psilocybin may have effects similar to other antidepressant treatments," says Professor David Nutt, senior author from Imperial College London "Psilocybin targets the serotonin receptors in the brain, just as most antidepressants do, but it has a very different chemical structure to currently available antidepressants and acts faster than traditional antidepressants."

The trial involved 12 patients (6 women, 6 men) with moderate to severe depression (average length of illness was 17.8 years). The patients were classified as having treatment-resistant depression, having previously had two unsuccessful courses of antidepressants (lasting at least 6 weeks). Most (11) had also received some form of psychotherapy. Patients were not included if they had a current or previous psychotic disorder, an immediate family member with a psychotic disorder, history of suicide or mania or current drug or alcohol dependence.

Patients attended two treatment days -- a low (test) dose of psilocybin 10mg oral capsules, and a higher (therapeutic) dose of 25mg a week later. Patients took the capsules while lying down on a ward bed, in a special room with low lighting and music, and two psychiatrists sat either side of the bed. The psychiatrists were present to provide support and check in on patients throughout the process by asking how they were feeling. Patients had an MRI scan the day after the therapeutic dose. They were followed up one day after the first dose, and then at 1, 2, 3, and 5 weeks and 3 months after the second dose.

The psychedelic effects of psilocybin were detectable 30 to 60 minutes after taking the capsules. The psychedelic effect peaked at 2-3 hours, and patients were discharged 6 hours later. No serious side effects were reported, and expected side effects included transient anxiety before or as the psilocybin effects began (all patients), some experienced confusion (9), transient nausea (4) and transient headache (4). Two patients reported mild and transient paranoia.

At 1 week post-treatment, all patients showed some improvement in their symptoms of depression. 8 of the 12 patients (67%) achieved temporary remission. By 3 months, 7 patients (58%) continued to show an improvement in symptoms and 5 of these were still in remission. Five patients showed some degree of relapse.

The patients knew they were receiving psilocybin (an 'open-label' trial) and the effect of psilocybin was not compared with a placebo. The authors also stress that most of the study participants were self-referred meaning they actively sought treatment, and may have expected some effect (5 had previously tried psilocybin before). All patients had agreement from their GP to take part in the trial. They add that patients were carefully screened and given psychological support before, during and after the intervention, and that the study took place in a positive environment. Further research is now needed to tease out the relative influence of these factors on symptoms of depression, and look at how psilocybin compares to placebo and other current treatments.

Writing in a linked Comment, Professor Philip Cowen, MRC Clinical Scientist, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK, says: "The key observation that might eventually justify the use of a drug like psilocybin in treatment-resistant depression is demonstration of sustained benefit in patients who previously have experienced years of symptoms despite conventional treatments, which makes longer-term outcomes particularly important. The data at 3 month follow-up (a comparatively short time in patients with extensive illness duration) are promising but not completely compelling, with about half the group showing significant depressive symptoms. Further follow-ups using detailed qualitative interviews with patients and family could be very helpful in enriching the assessment."

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160517083044.htm

Psychedelic drugs may reduce domestic violence

April 26, 2016

Science Daily/University of British Columbia

Psychedelic drugs may help curb domestic violence committed by men with substance abuse problems, according to a new UBC study.

The UBC Okanagan study found that 42 per cent of U.S. adult male inmates who did not take psychedelic drugs were arrested within six years for domestic battery after their release, compared to a rate of 27 per cent for those who had taken drugs such as LSD, psilocybin (commonly known as magic mushrooms) and MDMA (ecstasy).

The observational study followed 302 inmates for an average of six years after they were released. All those observed had histories of substance use disorders.

"While not a clinical trial, this study, in stark contrast to prevailing attitudes that views these drugs as harmful, speaks to the public health potential of psychedelic medicine," says Assoc. Prof. Zach Walsh, the co-director for UBC Okanagan's Centre for the Advancement of Psychological Science and Law. "As existing treatments for intimate partner violence are insufficient, we need to take new perspectives such as this seriously."

"Intimate partner violence is a major public health problem and existing treatments to reduce reoffending are insufficient," he says. "With proper dosage, set, and setting we might see even more profound effects. This definitely warrants further research."

The study was co-authored by University of Alabama Assoc. Prof. Peter Hendricks, who predicts that psilocybin and related compounds could revolutionize the mental health field.

"Although we're attempting to better understand how or why these substances may be beneficial, one explanation is that they can transform people's lives by providing profoundly meaningful spiritual experiences that highlight what matters most," says Hendricks. "Often, people are struck by the realization that behaving with compassion and kindness toward others is high on the list of what matters."

While research on the benefits of psychedelic drugs took place in the 1950 to the 1970s, primarily to treat mental illness, it was stopped due to the reclassification of the drugs to a controlled substance in the mid-1970s. Recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in psychedelic medicine.

"The experiences of unity, positivity, and transcendence that characterize the psychedelic experience may be particularly beneficial to groups that are frequently marginalized and isolated, such as the incarcerated men who participated in this study," says Walsh.

The study was published last week in the Journal of Psychopharmacology.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160426091744.htm

New study examines the effect of ecstasy on the brain

April 18, 2016

Science Daily/University of Liverpool

The effect ecstasy has on different parts of the brain has been the focus of recent study. Researchers found that ecstasy users showed significant reductions in the way serotonin is transported in the brain. This can have a particular impact on regulating appropriate emotional reactions to situations.

Researchers from the University of Liverpool have conducted a study examining the effect ecstasy has on different parts of the brain.

Dr Carl Roberts and Dr Andrew Jones, from the University's Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, and Dr Cathy Montgomery from Liverpool John Moores University conducted an analysis of seven independent studies that used molecular imaging to examine the neuropsychological effect of ecstasy on people that use the drug regularly.

A number of studies have compared ecstasy users to control groups on various measures of neuropsychological function in order to determine whether ecstasy use results in lasting cognitive deficits. It is common, however, for ecstasy users to use other drugs alongside the substance, and therefore the Liverpool team aimed to discover whether this had any bearing on the impact of the drug.

The nerve pathway that is predominantly affected by ecstasy is called the serotonin pathway. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that is synthesized, stored, and released by specific neurons in this pathway. It is involved in the regulation of several processes within the brain, including mood, emotions, aggression, sleep, appetite, anxiety, memory, and perceptions.

They found that ecstasy users showed significant reductions in the way serotonin is transported in the brain. This can have a particular impact on regulating appropriate emotional reactions to situations.

Dr Roberts, said: "The research team conducted the analysis on seven papers that fitted our inclusion criteria which provided us with data from 157 ecstasy users and 148 controls. 11 out of the 14 brain regions included in analysis showed serotonin transporter (SERT) reductions in ecstasy users compared to those who took other drugs.

"We conclude that, in line with animal data, the nerve fibres, or axons, furthest away from where serotonin neurons are produced (in the raphe nuclei) are most susceptible to the effects of MDMA. That is to say that these areas show the greatest changes following MDMA use.

"The clinical significance of these findings is speculative, however it is conceivable that the observed effects on serotonin neurons contribute to mood changes associated with ecstasy/MDMA use, as well as other psychobiological changes. Furthermore the observed effects on the serotonin system inferred from the current analysis, may underpin the cognitive deficits observed in ecstasy users.

"The study provides us with a platform for further research into the effect long term chronic ecstasy use can have on brain function."

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160418095916.htm

How LSD can make us lose our sense of self

April 13, 2016

Science Daily/Cell Press

When people take the psychedelic drug LSD, they sometimes feel as though the boundary that separates them from the rest of the world has dissolved. Now, the first functional magnetic resonance images (fMRI) of people's brains while on LSD help to explain this phenomenon known as "ego dissolution."

As researchers report in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on April 13, these images suggest that ego dissolution occurs as regions of the brain involved in higher cognition become heavily over-connected. The findings suggest that studies of LSD and other psychedelic drugs can produce important insights into the brain. They can also provide intriguing biological insight into philosophical questions about the very nature of reality, the researchers say.

"There is 'objective reality' and then there is 'our reality,'" says Enzo Tagliazucchi of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in Amsterdam. "Psychedelic drugs can distort our reality and result in perceptual illusions. But the reality we experience during ordinary wakefulness is also, to a large extent, an illusion."

Take vision, for example: "We know that the brain fills in visual information when suddenly missing, that veins in front of the retina are filtered out and not perceived, and that the brain stabilizes our visual perception in spite of constant eye movements. So when we take psychedelics we are, it could be said, replacing one illusion by another illusion. This might be difficult to grasp, but our study shows that the sense of self or 'ego' could also be part of this illusion."

It has long been known that psychedelic drugs have the capacity to reduce or even eliminate a person's sense of self, leading to a fully conscious experience, Tagliazucchi explains. This state, which is fully reversible in those taking psychedelics, is also known to occur in certain psychiatric and neurological disorders.

But no one had ever looked to see how LSD changes brain function. To find out in the new study, Tagliazucchi and colleagues, including Robin Carhart-Harris of Imperial College London, scanned the brains of 15 healthy people while they were on LSD versus a placebo.

The researchers found increased global connectivity in many higher-level regions of the brain in people under the influence of the drug. Those brain regions showing increased global connectivity overlapped significantly with parts of the brain where the receptors known to respond to LSD are found.

LSD also increased brain connectivity by inflating the level of communication between normally distinct brain networks, they report. In addition, the increase in global connectivity observed in each individual's brain under LSD correlated with the degree to which the person in question reported a sense of ego dissolution.

Tagliazucchi notes in particular that they found increased global connectivity of the fronto-parietal cortex, a brain region associated with self-consciousness. In particular, they observed increased connection between this portion of the brain and sensory areas, which are in charge of receiving information about the world around us and conveying it for further processing to other brain areas.

"This could mean that LSD results in a stronger sharing of information between regions, enforcing a stronger link between our sense of self and the sense of the environment and potentially diluting the boundaries of our individuality," Tagliazucchi said.

They also observed changes in the functioning of a part of the brain earlier linked to "out-of-body" experiences, in which people feel as though they've left their bodies. "I like to think that our experiment represents a pharmacological analogue of these findings," he says.

Tagliazucchi says the findings highlight the value of psychedelic drugs in carefully controlled research settings. He plans to continue to use neuroimaging to explore various states of consciousness, including sleep, anesthesia, and coma. He also hopes to make direct comparisons between people in a dream versus a psychedelic state. Meanwhile, researchers at the Imperial College London are investigating other psychedelic drugs and their potential use in the treatment of disorders including depression and anxiety.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160413135656.htm

Brain on LSD revealed: First scans show how the drug affects the brain

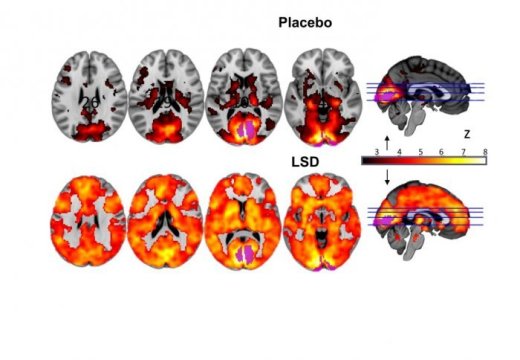

The areas that contributed to vision were more active under LSD, which was linked to hallucinations. Credit: Image courtesy of Imperial College London

April 11, 2016

Science Daily/Imperial College London

For the first time, researchers have visualized the effects of LSD on the human brain. In a series of experiments, scientists have gained a glimpse into how the psychedelic compound affects brain activity. The team administered LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) to 20 healthy volunteers in a specialist research centre and used various leading-edge and complementary brain scanning techniques to visualize how LSD alters the way the brain works.

Researchers from Imperial College London, working with the Beckley Foundation, have for the first time visualized the effects of LSD on the human brain.

In a series of experiments, scientists have gained a glimpse into how the psychedelic compound affects brain activity. The team administered LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) to 20 healthy volunteers in a specialist research centre and used various leading-edge and complementary brain scanning techniques to visualize how LSD alters the way the brain works.

The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reveal what happens in the brain when people experience the complex visual hallucinations that are often associated with LSD state. They also shed light on the brain changes that underlie the profound altered state of consciousness the drug can produce.

A major finding of the research is the discovery of what happens in the brain when people experience complex dreamlike hallucinations under LSD. Under normal conditions, information from our eyes is processed in a part of the brain at the back of the head called the visual cortex. However, when the volunteers took LSD, many additional brain areas -- not just the visual cortex -- contributed to visual processing.

Dr Robin Carhart-Harris, from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, who led the research, explained: "We observed brain changes under LSD that suggested our volunteers were 'seeing with their eyes shut' -- albeit they were seeing things from their imagination rather than from the outside world. We saw that many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD -- even though the volunteers' eyes were closed. Furthermore, the size of this effect correlated with volunteers' ratings of complex, dreamlike visions. "

The study also revealed what happens in the brain when people report a fundamental change in the quality of their consciousness under LSD.

Dr Carhart-Harris explained: "Normally our brain consists of independent networks that perform separate specialised functions, such as vision, movement and hearing -- as well as more complex things like attention. However, under LSD the separateness of these networks breaks down and instead you see a more integrated or unified brain.

"Our results suggest that this effect underlies the profound altered state of consciousness that people often describe during an LSD experience. It is also related to what people sometimes call 'ego-dissolution', which means the normal sense of self is broken down and replaced by a sense of reconnection with themselves, others and the natural world. This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way -- and seems to be associated with improvements in well-being after the drug's effects have subsided."

Dr Carhart-Harris added: "Our brains become more constrained and compartmentalized as we develop from infancy into adulthood, and we may become more focused and rigid in our thinking as we mature. In many ways, the brain in the LSD state resembles the state our brains were in when we were infants: free and unconstrained. This also makes sense when we consider the hyper-emotional and imaginative nature of an infant's mind."

In addition to these findings, research from the same group, part of the Beckley/Imperial Research Programme, revealed that listening to music while taking LSD triggered interesting changes in brain signalling that were associated with eyes-closed visions.

In a study published in the journal European Neuropsychopharmacology, the researchers found altered visual cortex activity under the drug, and that the combination of LSD and music caused this region to receive more information from an area of the brain called the parahippocampus. The parahippocampus is involved in mental imagery and personal memory, and the more it communicated with the visual cortex, the more people reported experiencing complex visions, such as seeing scenes from their lives.

PhD student Mendel Kaelen from the Department of Medicine at Imperial, who was lead author of the music paper, said: "This is the first time we have witnessed the interaction of a psychedelic compound and music with the brain's biology.

The Beckley/Imperial Research Programme hope these collective findings may pave the way for these compounds being one day used to treat psychiatric disorders. They could be particularly useful in conditions where negative thought patterns have become entrenched, say the scientists, such as in depression or addiction.

Mendel Kaelen added: "A major focus for future research is how we can use the knowledge gained from our current research to develop more effective therapeutic approaches for treatments such as depression; for example, music-listening and LSD may be a powerful therapeutic combination if provided in the right way."

Professor David Nutt, the senior researcher on the study and Edmond J Safra Chair in Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial, said: "Scientists have waited 50 years for this moment -- the revealing of how LSD alters our brain biology. For the first time we can really see what's happening in the brain during the psychedelic state, and can better understand why LSD had such a profound impact on self-awareness in users and on music and art. This could have great implications for psychiatry, and helping patients overcome conditions such as depression."

Amanda Feilding, Director of the Beckley Foundation, said: "We are finally unveiling the brain mechanisms underlying the potential of LSD, not only to heal, but also to deepen our understanding of consciousness itself."

The research involved 20 healthy volunteers -- each of whom received both LSD and placebo -- and all of whom were deemed psychologically and physically healthy. All the volunteers had previously taken some type of psychedelic drug. During carefully controlled and supervised experiments in a specialist research centre, each volunteer received an injection of either 75 micrograms of LSD, or placebo. Their brains were then scanned using various techniques including fMRI and magnetoencephalography (MEG). These enabled the researchers to study activity within the whole of the brain by monitoring blood flow and electrical activity.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/04/160411153006.htm

Mouse model yields possible treatment for autism-like symptoms in rare disease

Anti-anxiety drug clonazepam reduces autistic features in mouse model of Jacobsen syndrome

https://www.sciencedaily.com/images/2016/03/160316082732_1_540x360.jpg

March 16, 2016

Science Daily/University of California - San Diego

About half of children born with Jacobsen syndrome, a rare inherited disease, experience social and behavioral issues consistent with autism spectrum disorders. Researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and collaborators developed a mouse model of the disease that also exhibits autism-like social behaviors and used it to unravel the molecular mechanism that connects the genetic defects inherited in Jacobsen syndrome to effects on brain function.

The study, published March 16, 2016 in Nature Communications, also demonstrates that the anti-anxiety drug clonazepam reduces autistic features in the Jacobsen syndrome mice.

"While this study focused on mice with a specific type of genetic mutation that led to autism-like symptoms, these findings could lead to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying other autism spectrum disorders, and provide a guide for the development of new potential therapies," said study co-author Paul Grossfeld, MD, clinical professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and pediatric cardiologist at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego.

Jacobsen syndrome is a rare genetic disorder in which a child is born missing a portion of one copy of chromosome 11. This gene loss leads to multiple clinical challenges, such as congenital heart disease, intellectual disability, developmental and behavioral problems, slow growth and failure to thrive.

Previous research by Grossfeld and colleagues suggested that PX-RICS might be the missing chromosome 11 gene that leads to autism in children with Jacobsen syndrome. To investigate further, Grossfeld contacted University of Tokyo researchers who had already been studying PX-RICS for its role in brain development, but were unaware of the link to autism in humans.

In this study, the Japanese researchers determined that PX-RICS is most likely the gene responsible for autism-like symptoms in Jacobsen syndrome. To do this, they performed several well-established tests that measure common autism symptoms -- anti-social behavior, repetitive activities and inflexible adherence to routines. As compared to normal mice, mice lacking PX-RICS spent less time on social activities (e.g., nose-to-nose sniffing and huddling) and were more apathetic or avoidant when approached by a stimulator mouse. PX-RICS-deficient mice also spent more than twice as much time on repetitive behaviors such as self-grooming and digging than normal mice. In addition, mice lacking PX-RICS more closely adhered to a previously established habit and were less able to adapt their behavior in novel situations.

Grossfeld's colleagues in Tokyo also explored the molecular mechanism connecting lack of PX-RICS to behavior. They found that mice lacking the PX-RICS gene were also deficient in GABAAR, a protein crucial for normal neuron function. That observation inspired the researchers to test clonazepam, a commonly used anti-anxiety drug that works by boosting GABAAR, as a potential treatment for autism-like symptoms in these Jacobsen syndrome mice.

PX-RICS-deficient mice treated with low, non-sedating doses of clonazepam behaved almost normally in social tests, experienced improvements in learning performance and were better able to deviate from established habits.

"We now hope in the future to carry out a small pilot clinical trial on people with Jacobsen syndrome and autism to determine if clonazepam might help improve their autistic features," Grossfeld said.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/03/160316082732.htm

New technique could more accurately measure cannabinoid dosage in marijuana munchies

March 15, 2016

Science Daily/American Chemical Society

As more states decriminalize recreational use of marijuana and expand its medical applications, concern is growing about inconsistent and inaccurate dosage information listed on many products, including brownies and other edibles. But now scientists report that they have developed a technique that can more precisely measure cannabis compounds in gummy bears, chocolates and other foods made with marijuana. They say this new method could help ensure product safety in the rapidly expanding cannabis retail market.

The researchers present their work today at the 251st National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

"Producers of cannabis edibles complain that if they send off their product to three different labs for analysis, they get three different results," says Melissa Wilcox, who is at Grace Discovery Sciences. "The point of our work is to create a solid method that will accurately and reliably measure the cannabis content in these products."

More than 30 states and the District of Columbia have either decriminalized cannabis or have allowed legal medical access to it. One recent study has shown that where marijuana edible products are legally available, labeling is at best inconsistent and at worst misleading. In fact, researchers who recently analyzed cannabis products legally purchased in three U.S. cities found that only 17 percent of the tested edibles containing marijuana had labels that accurately listed the amount of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the active ingredient in marijuana that causes the substance's "high." More than half had detectable levels of another marijuana compound called cannabidiol, or CBD. This substance, which can be used as a pain-reliever and an anti-inflammatory without mind-altering effects, wasn't listed on most of these labels.

These discrepancies are important. Edible marijuana can be more potent and can have longer lasting effects than if it is smoked because of how it is metabolized in the body, says Jahan Marcu, Ph.D., who is at Americans for Safe Access and is vice-chair of the newly formed ACS Cannabis Subdivision. It also takes longer for a person eating a marijuana-containing snack to feel its effects.

"It's a lot easier for an individual to control their dose when smoking," Wilcox says. "The effects of edibles can take a while to happen. You eat them, and then wait to see how you feel in an hour or two. If you ingested too much, you could be in for an unexpectedly bad experience."

Most marijuana edibles are currently analyzed using a device called a high performance liquid chromatograph, or HPLC. But there's a problem using this technique.

"These machines were never designed for you to inject a cookie into them," Marcu says. "The sugars, starches and fats will wreak havoc on HPLC equipment. They can really muck up the works and lead to inaccurate results."

To overcome this problem, Wilcox, Marcu and colleagues placed food samples infused with cannabis into a cryo-mill with dry ice or liquid nitrogen. Then they added abrasive diatomaceous earth -- a silica-based compound sometimes used to keep snails out of gardens -- and ground the mixture to create a homogenous sample. They separated out the various chemical components using a technique called flash chromatography. This allowed them to inject liquid containing only the cannabinoids into an HPLC for analysis. The researchers concluded this process could yield far more accurate and reliable measurements of THC and/or CBD levels in an edible product than was previously possible.

The team is still evaluating their preliminary results and determining whether this technique will work with all cannabis-infused food and drinks. But so far, it appears to accurately measure cannabis content in gummy bears, brownies, cookies and certain topical lotions. According to Marcu, the next step is to install this equipment into commercial labs and train technicians to use it on a larger scale.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/03/160315085618.htm